Michiana's world of nuclear energy from research to policy

SOUTH BEND, Ind. – In the United States, 20 percent of all generated electricity comes from nuclear energy produced from the 99 reactors around the country.

Here in Michiana, two of those facilities are nestled along Lake Michigan. Most notably, Donald C. Cook Nuclear Plant located in Bridgman.

With both reactors operating at full power, the plant can produce enough energy to supply more than 1.5 million homes in southwest Michigan and northwest Indiana.

The greatest benefit of nuclear energy, according to Indiana Michigan Power, is the preservation of air quality as fission doesn’t produce emissions.

However, there has to be a byproduct of some sort. Researchers and energy officials call this nuclear waste “spent nuclear fuel.”

But is it really “waste”?

A professor and decorated researcher at the University of Notre Dame has a different perspective on the issue that has plagued the U.S. since the Cold War.

Dr. Peter Burns believes in reprocessing the fuel. “In reality, we’ve only recovered about 1 percent of the energy we could. The fuel isn’t spent at all, it’s really just dirty,” said Burns.

In his research, it all comes down to chemical properties and how uranium interacts with water.

Burns has created several versions of uranium nanoclusters that would effectively change the future of n

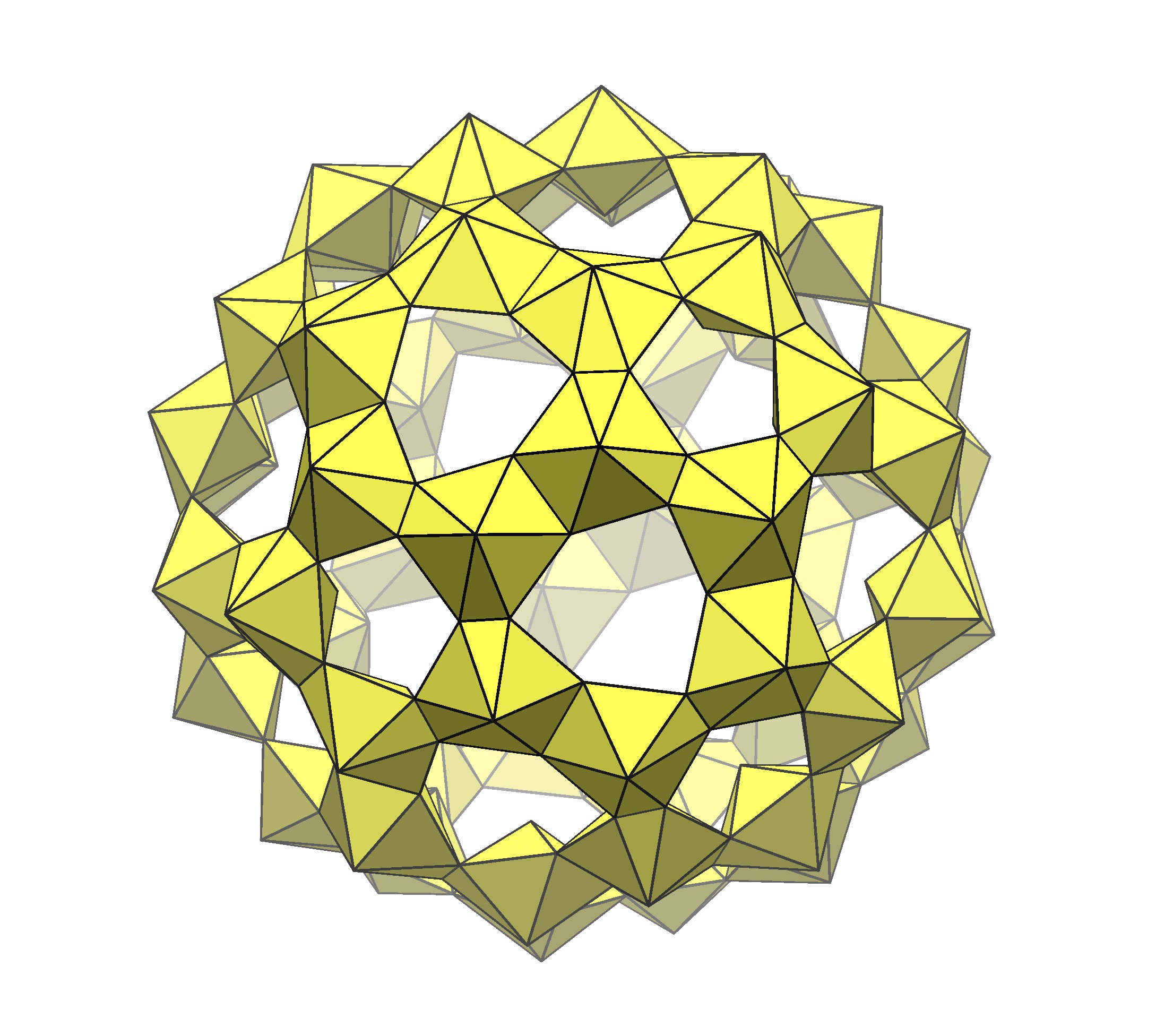

uclear energy for producers and consumers.His favorite of all? U60

“Its perhaps the most beautiful and most famous,” he said as he admired a 3-dimensional print of the molecule.

His discovery works on the basis of extraction by size, not chemicals, which will simplify the chemistry.

Burns explained, “If you were to put spent nuclear fuel into a cup of water, nothing would happen. Actually, it might bubble because of the intense radioactivity.”

He went on to say if a concoction of acidic chemicals were added to the water, the dissolution would begin.

The difference is, U60 doesn’t require organic chemicals to dissolve.

“If I simply take water and I create the conditions to form this cluster [U60] in solution, I can dissolve the fuel no problem,” he said. “I could take advantage of their size or their mass to separate them rather than doing a chemical separation using kerosene and stuff. I could maybe do a separation on their size and that would simplify my chemistry a lot so I would produce much less radioactive waste.”

Burns’ technology is already being used in other countries like France that have been reprocessing spent nuclear fuel for the last several decades.

What about here at home?

According to I&M Spokesperson Bill Schalk, Cook Nuclear currently stores their spent fuel in dry storage casks and pools of water that are filled with 1.5 million gallons of water from Lake Michigan drawn into the plant every minute.

Once stored away, the fuel is hauled off to a tightly guarded area on the property.

Schalk said the casks, made of steel and concrete don’t give off as much radiation as you think. In fact, if you were to hug the cask for an hour, you would receive less radiation than an x-ray at the doctor’s office.

That doesn’t mean that exposure is not a health or environmental risk.

The government has been back and forth about a permanent repository for nuclear disposal since Yucca Mountain’s proposal in 1987.

“Spent fuel, for example, is almost entirely UO2. Its 96 or 97 percent UO2 -- uranium oxide. So what happens when you put uranium oxide in a Yucca Mountain environment? How does it weather or alter with time? If it doesn’t, you have no problem because the radio nucleides can’t get out. When it does, this is when you have potential exposure,” explained Burns.

Through several administrations, the safer and perhaps more environmentally-friendly option of reprocessing has been pushed to the wayside due to concerns about plutonium recovery which would make nuclear weapons easier to develop, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

"The short answer starts when the Carter administration issued a policy that ended U.S. work on reprocessing, due to concerns about proliferation of nuclear weapons. The Reagan administration revised the policy to allow reprocessing, but decided against further work on the topic. The nation’s efforts since that point have focused on a permanent repository for spent nuclear fuel from U.S. commercial nuclear power plants," said Scott Burnell, public affairs officer of the NRC.

Turning the attention back on geologic isolation

As of May 10, 2018, the Yucca Mountain Repository got the green light to being the licensing process to become the nation’s permanent nuclear waste disposal site.

ABC News reported the 147,000 acre area designated by the U.S. Congress, would be safe as exposure potential is lowered due to its isolation in Nevada’s desert.

The experts, Schalk and Burns, agree that geologic isolation is the second best option.

As for the science of reprocessing, it’s there. They say it’s the policy that would have to catch up.

“I think the bigger issue is a long-term view by the country of what the electric picture is going to look like. The problem is the planning horizon to do this is so long, that you need some policy that would get you past those changing whims at it were of politicians and policy where you just pick a path and go for it and get there as the French have done,” said Schalk.

“Oh, it’s entirely a policy issue. We can do it,” said Burns. “I would rather we treat the spent fuel at Cook as a national treasure because of the huge amount of energy that’s in it that we can have.”

Burns noted if the world collectively reprocessed spent nuclear fuel, there would be enough to produce worldwide renewable nuclear energy for the next 5,000 years.

The science is only half of the battle

“There would be an enormous regulatory process that would have to take place. It’s the next step to get through both the cost and the regulatory process up front to get to the point where it was economically viable,” said Schalk.

Schalk said Cook Nuclear will continue to effectively and safely cater to the short-term needs of their nuclear waste while the long term solution is being worked out on Capitol Hill.

For Burns, he and his students are continuing to create new materials and understand more about uranium and discover new knowledge.